- Home

- Thomas E. Simmons

The Man Called Brown Condor Page 8

The Man Called Brown Condor Read online

Page 8

“Yes, sir, Mr. Snyder.”

“It better be. I had a student freeze up on the controls once. He damn near killed us both. You’ve passed the ground school so I’m told. I assume you know something about what makes a plane fly and what the controls are for. You’re going to take off, climb to thirty-five hundred feet, do some turns, some straight and level, climbs and descents, and some stalls in order to give you a feel for the aircraft, introduce you to all the maneuvers you studied in the book. Remember, if I wiggle the stick or you feel me on the controls, let me take over. Any questions?”

“No, sir.”

“Then crawl into the rear cockpit. A lineman will give us a prop. I assume you know the drill.”

Before getting into the front cockpit, Snyder checked to be sure John’s safety harness was securely fastened. He motioned over a lineman, got in the front cockpit, and fastened his own seat belt.

The lineman called out, “Off and closed.”

Snyder spoke into the Gosport tube, “Answer him, Robinson!”

John went through the starting procedure. “Off and closed.”

The lineman called, “Brakes and contact!”

This training plane had a tail wheel and small heel brake petals on the floor beneath the rudder controls. John pushed the brake petals, cracked the throttle opened, switched on the magnetos and repeated, “Brakes and contact.”

The lineman swung the prop. The air-cooled, radial engine caught after one or two smoky burps and settled down to a throaty, syncopated rhythm, giving off the peculiar hot oil smell John had noticed in Robert Williamson’s WACO.

The faraway sound of Snyder’s voice coming through the speaking tube instructed John to stay lightly on the controls through the taxi and takeoff.

Snyder began to taxi the plane in a snake-like “S” course down the field. “Notice with the tail on the ground you can see nothing directly ahead because the plane’s nose blocks your vision. That’s why we ‘S’ taxi so you can see ahead a few degrees off each side of the nose as we work our way forward. On the takeoff roll, as we gain speed, you push the stick a little forward to lift the tail. Stay off the brakes! Once the tail comes up you can see straight ahead over the nose. The same holds true for landing. Once you flare for landing, you won’t be able to see a thing ahead. You’ll have to use your peripheral vision to keep the plane rolling straight with rudder until it has slowed enough to taxi ‘S’ turns safely.” Snyder’s voice sounded funny coming through the Gosport tube as he continued to shout commands

Snyder let John try his hand at taxiing. The voice again, “Even out your ‘S’ turns, Robinson! You’re all over the place!” Jack Snyder took back the controls. At the far end of the field he turned the plane completely around to check the sky for landing traffic. Satisfied, Snyder turned the plane upwind. “Stay lightly on the controls during the takeoff, get the feel of them,” the Gosport voice ordered. Snyder advanced the throttle. The plane had hardly lifted into the air when John felt the stick shake. The voice from the little tube, shouting over the engine and wind noise, commanded, “You have the airplane. Climb to four hundred feet and turn to the left ninety degrees. Then climb to eight hundred feet and turn forty-five degrees to the right and climb straight ahead to thirty-five hundred feet. Don’t let the nose get above the horizon and keep an eye out for other planes!”

John put his left hand on the throttle, his right on the stick, his feet on the rudder petals, and began a timid turn to the left.

“Use your rudder, damnit!” shouted the voice in his ears. “Watch the nose! You’re letting it drop.” A moment later, “Now the nose is too high.”

Each comment was followed by an unmistakable firm corrective movement of the controls momentarily over-riding John’s stiff, clumsy attempts to perform the maneuvers. After a period of too much up followed by too much down, John began to settle the plane into a more or less steady climb.

“Robinson,” the little voice returned. “Don’t you think we could stop climbing now? We’re at four thousand feet. I told you to level off at thirty-five hundred feet. Ease off that throttle and get back down to thirty-five hundred.” There was a pause, then, “Don’t dive it, damnit!” It was followed by, “Now you’re climbing again. Get this thing in a glide and hold it with a steady airspeed! Show me you know the difference between a glide and a dive.”

With much effort at changing altitude while watching for traffic and checking the altimeter and airspeed every few seconds, John found himself proudly flying straight and level at thirty-five hundred feet. The feeling was short-lived.

The commands came fast and often. “Turn to the right. Rudder, damnit! Use the rudder! You have to use the rudder and the stick together. Now turn left. Watch the nose! Use the stick! Get this thing back to level! Look at your airspeed, for Christ’s sake! You’re supposed to be at thirty-five hundred feet, so get the hell back up there!”

John was sweating and doing his own share of swearing, more at himself than at the voice that constantly assaulted his ears over the roar of the engine.

“All right, Robinson, let’s try a few stalls. You studied about stalls in the book? Too little airspeed and/or too great an angle of attack and the wings stall. Remember? You now have the opportunity to study them up close.” Johnny felt the stick move back. The plane changed from level flight to a nose-high attitude. “Okay, you take it and hold it there.” The stick wiggled. John grasped it and put his feet back on the rudder pedals. “When you feel the plane buffet and the nose begin to drop, remember to move the stick forward, get the nose down, add power, and get the wings flying again. You’ve got the airplane.”

John felt it was the other way around. The plane began to buffet and suddenly the nose fell out from under him. At the same time, the left wing dropped and was followed by a sickening descent that left John’s stomach somewhere above. His eyes wildly stared over the nose straight down at the earth.

His first reactions were all wrong. He jerked back on the stick, forgot to push in the throttle, and tried to pick up the low wing with aileron instead of rudder. He felt a great desire to wet his pants.

The voice again, “Get that nose down! Give it full throttle! Get this thing flying again! Use a little rudder. I said a little! Get off the ailerons! You put in too much rudder or aileron in a stall and you’ll wind up in a spin, maybe on your back.”

John pushed the stick forward. With the earth rising rapidly toward him, it seemed an unnatural thing to do, but he did it and held the stick there. He got off the aileron and remembered to use a little opposite rudder to get the low wing level. The airspeed began to build and he was flying again but in a dive. He eased the throttle back a little.

“All right. Now ease the stick back and get us level again.”

With the ground still rushing up at him, John pulled the stick back too rapidly and too far. The G-force of the pullout pushed him down in his seat; his cheeks began to sag.

“Ease it, damnit! You jerk back on the stick like that in a high speed dive and you’ll get a secondary stall or pull the wings off this thing.”

John eased the stick pressure and found himself in straight and level flight. He was much relieved—for the moment. For the first time he looked out at the beautiful sky and the green fields below. The tension in his mind and body began to fade. He was flying!

Then the voice came at him again. “Okay. Now let’s try a power-on stall from a climbing turn, shall we?”

Robinson’s stomach, which had only just caught up with him, tightened in a knot as he reluctantly eased the plane back to altitude. Following instructions, he found himself at full power in a steep climbing turn to the left. When the buffet began and the nose dropped, John thought he would be ready—terrified but ready—and he was. He got the stick forward, left the power at full, and managed to catch a wing drop, bringing the plane back to normal straight and level flight. Oh! Please let’s go home now. He was worn-out.

“That was better,” the voice said.

“Now let’s try one to the right.”

John groaned and felt his stomach do a flip. As instructed, he pushed the throttle full forward and began a steep climbing turn to the right. This time, just as the plane began to buffet, Snyder slammed the right rudder pedal full forward. The plane whipped viciously over on its back. The nose dropped straight toward the earth, which began spinning rapidly before the wide-eyed stare of the panic-stricken Robinson.

John couldn’t help but cry out, his shout torn away into the screaming wind. He felt himself pressed down into his seat. He could barely hear the amazingly calm voice from the tube. “Rudder, damnit! Left rudder! We’re in a spin to the right. Neutralize the stick! Pull the throttle back! Do it now! You hear me, boy?”

The “boy” got through to him. John shouted in his mind, I’m not a nigger, you hear me? Anger overcame fear and John’s mind began to work again. He pushed in full left rudder, relaxed back pressure on the stick, and pulled the throttle off. At first nothing happed. The plane continued its sickening rotation as it spun toward the earth. Panic clawed at him but he held opposite rudder and neutral stick. It’s what the book said to do. The rotation began to slow. Another turn and the plane stopped spinning, airspeed increased, and with shaking knees and hands, John eased the plane back to level flight.

“All right,” the voice said. “There’s the field over there to the left. I’ll take it now. You follow me through on the controls and pay attention to the landing pattern, left downwind at eight hundred feet, turn left base down to four hundred feet, turn final for the last four hundred feet. You got that? And don’t forget to look for traffic. I don’t care to die in a midair collision. And keep your feet off the brakes.”

John released what had been a death grip on the stick. He was covered in sweat. His mouth was dry as cotton. He could feel the convulsions rising up from his stomach. He leaned over the edge of the cockpit and vomited in mixed agony and relief. The spittle was sucked from his lips by the slipstream rushing past. The contents of his stomach flowed back down the fuselage. Spittle spread over his chin, cheeks, and nose like rain over a windshield. He wiped his mouth with his sleeve and wiggled the stick to let Snyder know he was still willing to fly. Surprisingly, Snyder let him fly down to landing pattern altitude before taking over. Robinson kept his hands and feet on the controls to get the feel of landing.

John hardly remembered the touchdown and taxi to the flight line. The sudden silence after the engine stopped snapped him back to time and place. The flight was over. He was relieved, but his arms and legs felt so heavy, he wasn’t sure he could pull himself out of the cockpit. He unfastened his seat belt and removed his helmet. He struggled out of the plane and climbed down from the wing, his clothes stained with sweat and vomit.

Snyder stood before him, calm, neat, dressed in immaculate khaki jodhpurs, white shirt, black tie, leather jacket, and polished brown boots.

“Same time day after tomorrow, Robinson. That is, unless you decide to quit.”

John looked at the instructor. “I been wantin’ to fly all my life, and if I can’t learn to fly because of you, Mr. Snyder, then I’m gonna learn to fly in spite of you and all them that thinks I’m a joke.”

To John’s surprise, he thought he detected a slight smile on Snyder’s face.

“You just might do that. Now go get that bucket and rag over there by the hangar and clean off the side of this airplane. You’re pretty much a mess, too. If you want to leave by the gate, I’ll log you in, save you a little embarrassment. Next time, bring a paper bag with you.”

“Thank you, Mr. Snyder. I won’t need no paper bag. I’m gonna be a pilot.”

“Day after tomorrow, Robinson.”

Snyder turned and left John alone with a very messy airplane. It didn’t matter. John felt a little shaky but determined to have his dream. He filled the bucket with water, picked up the rag, and began to clean the airplane.

John had intended to catch up on work at his garage after his flying lesson, but he was worn out and still felt a bit queasy. To avoid any friends who might be hanging around to hear about his first flying lesson, he took the back stairs to his room and crawled onto his cot. Staring up at the unpainted ceiling, he couldn’t shut down the voices arguing in his mind. One kept telling him that flying wasn’t worth feeling so bad, that he couldn’t go up again and go through that spinning misery. Somewhere a voice echoed in his mind. Look at you! You can’t even make your supper, much less eat it. They ain’t gonna let a nigger learn to fly. Whoever heard of such a thing? But another voice cried out, You gonna stick it out! You gonna fly, damn it! Finally the voices stopped. John drifted off to sleep.

There were other voices that afternoon, voices at the flight line shack. A group of instructors and a few students were sitting around, some filling out log books, others drinking coffee.

“Did you see that nigger cleaning off the side of the plane? Snyder must have put him through the wringer.”

“Hell, that must’ve been them I saw spinning. I thought they were out of control and might go in.”

“If Snyder put him through it, I don’t think we’ll see any more nigger students out here. Snyder wasn’t too happy when he drew him, you know.”

“I got twenty dollars says the nigger never shows up for another lesson. Anyone want to cover that?”

From a chair over in the corner, Bill Henderson said, “I’ll take ten dollars of that bet.”

“Hell, Henderson, from what I hear, it’s your fault he made it this far. Anyone want to put another ten bucks on the nigger?”

From the doorway someone replied, “Yeah. I’ll cover the other ten.”

Everyone in the room looked toward the door to see Snyder reaching into his hip pocket.

“Here’s my ten, Smitty.” He handed the bill to one of the men up front. “Pass it back to him.” Snyder turned to the blackboard to check the day’s schedule, then walked out the door toward the flight line for his last student of the day.

Robinson did show up for his next lesson and for every one that followed. Snyder dropped his sarcasm, never used the word “nigger” again, but never let up on the instruction. He continued to shout through the Gosport tube, hammering out the rudiments of airmanship to the intensely determined Robinson. Snyder was hard on his students because he knew flying was no game. It was a serious endeavor that could kill you quick if you got sloppy.

Near the end of the eighth flight hour, an hour that had been spent practicing endless circuits of touch-and-go landings, Snyder wiggled the stick and took over the controls. He landed the plane, turned it around, taxied back to the end of the field, and brought it to a stop just clear of the touchdown area.

The engine was ticking over at idle. John watched Snyder get out of the front cockpit and step down from the plane. Something must be wrong. What did I do? John checked the engine instruments. They all looked normal. It must be something I did. Lord, don’t let him ground me.

He was looking down at the controls, trying to hear or feel what was amiss, when he heard the impatient voice of his instructor.

“Well Robinson, what are you waiting for?”

John looked at him with a blank expression on his face.

“You going to sit there all day confusing everyone who wants to land sometime this afternoon, or are you going to fly this thing?”

John’s expression changed from blank to startled and comprehending.

“Now remember,” Snyder continued, “do just what you’ve been doing all day. I want you to take off, come around for one touch-andgo, then on the next circuit make a full-stop landing and taxi back here to pick me up. Don’t forget to look for other traffic in the pattern. You got that?”

“Yes, sir.”

“We’ll see.” Snyder turned and walked away.

John stared at him for a second and then looked up front at the empty cockpit. His palms were sweaty. Sitting in the airplane alone, he had a flash of self-doubt. He heard the faint echo of his mother’

s voice, You got no business fooling ’round with no flying machine. He thought he heard a voice say, The white boss man leaving you, boy. This here machine gonna bite you.

Johnny wiped his hands on the knees of his britches and carefully went though the simple checkout of the engine and controls that had been pounded into habit. Then he craned his head around to check for any landing traffic. There was none. He looked in Snyder’s direction, seeking a last official “go ahead.” His instructor was standing near the fence, legs apart, his back to Johnny, relieving himself.

Well, hell then! John eased the throttle full forward. All his thoughts were now concentrated on making a smooth takeoff. The propeller clawed at the air. The plane rushed at the wind. John had hardly gotten the tail up when the wheels stopped bouncing and the turf quickly dropped away. Without Snyder’s weight in the front cockpit, the takeoff roll was much shorter and the plane climbed faster.

For the first time there was no distant voice from the little tube. God Almighty! You flying this thing Johnny Robinson! John whooped and shouted, reached out into the slipstream, and beat his hand on the side of the plane as if to urge his winged steed onward. His senses filled with the moment—the sounds, the smells, the rush of air, the beauty of the earth spreading out below him. It was a moment of exhilaration that would stay in his memory forever: his first solo flight.

His landing was not too good but it didn’t matter. He had flown solo. Self-confidence is born from such acts. He would work harder now to smooth out his novice technique. He would be a pilot.

John taxied to the corner of the field where Snyder was waiting.

“All right, Robinson, now that we’ve got that over with, maybe you can settle down and learn how to fly an airplane. If you think the undercarriage won’t collapse on us after that last landing, taxi back to the ramp and I’ll buy you a cup of coffee.”

“Yes, sir!” John tried to look serious, but he couldn’t get the grin off his face. There was something else that happened that day. Back at the line shack, he got more than coffee. He got handshakes and was congratulated all around. The other students no longer made it a point to shun him, always stand apart from him. He was accepted as a fellow student, a fellow flyer.

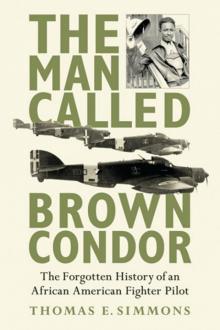

The Man Called Brown Condor

The Man Called Brown Condor