- Home

- Thomas E. Simmons

The Man Called Brown Condor Page 4

The Man Called Brown Condor Read online

Page 4

“A couple of people I know say you’re not a bad mechanic, better than average. That’s saying something in Detroit, especially you being black.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

“I could use somebody like you.”

John remained silent.

“How much they pay you over where you work?”

John told him.

“That’s an honest answer. I already knew what you make. You told me something different trying to jack me up, you’d be outta here.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I need a mechanic that really knows what he’s doing. I got one good mechanic with a helper, but they can’t keep up with the work no more. Business growing, see? I got three trucks and eight taxis. I plan to add on another truck and four more taxis. When they need fixing, they need fixing right and fast. Trucks and taxis don’t make me a dime sitting in this garage, see?”

“No, sir. I reckon not.”

“I tell you what. I’ll pay you twice what you been making. You keep ’em running and you got a solid job, provided you show up on time and do the work eight till five, six days a week, and maybe nights sometimes if I need you. You want the job?”

“I’ll take it, Mr. . . . ” John paused.

“You just call me Boss.”

“Yes, sir. Boss. I should give my old boss two weeks notice.”

“I like that. Loyalty. But if you want the job, you start next Monday. One more thing. I don’t like my business getting out on the street. My people keep their mouths shut. You understand what I’m saying?”

“Yes, sir.”

John’s old boss said he would be sorry to see him go, but that he could not compete with the pay. Then he said something John thought was a little peculiar.

“Johnny, I know the money’s good, but don’t do nothing for Fitzgerald other than keeping his taxis and trucks rolling. Don’t drive for him, don’t poke around in his business, and don’t ask questions. Just keep a tight lip and do your job.”

John had not known that his new boss’s name was Fitzgerald, but he was quick to understand the advice. After he went to work, he learned that Mr. Fitzgerald’s trucks worked mostly at night. The drivers that brought them in for work or picked them up didn’t have much to say. It was pretty easy for John to figure things out. Prohibition had been passed in 1919. Whiskey was illegal in the United States but not next door in Canada. He knew that bootleg whiskey flowed south across the Canadian border through Detroit—boat and truckloads of it. Around the garage no one gave him any trouble. He did his job, got along, rarely spoke. That earned him the sobriquet “tight-lipped Johnny.” It also kept him out of trouble.

John put most of his pay in the bank. He moved into a three-room, cold water flat that had a bedroom, a tiny kitchen with a sink and an icebox, and a small sitting room. It was equipped with electric lights and had an oil stove for cooking and heating. There was a bathroom in the hall that he shared with the flat next door.

Robinson was not all work and no play. The girls knew Johnny was in town. On Saturday nights, in certain quarters of the town, John gained a reputation as a smooth dancer. In the flashy age of flappers, jazz, and speakeasies, the ladies were not slow to notice the tall, quiet, confident man who had nice manners, dressed well, and could make a girl look good on the dance floor.

For those who knew him, there was a certain restlessness about Johnny, a restlessness that seemed more than just the desire to succeed in his trade. He continued to learn and study. He built a bookcase in his flat and filled it with books and manuals on mechanics and those he could find about managing a business. A few books and magazines on aviation began to appear. John knew what was eating at him. During his years of school, he had put away what his mother had referred to as “that foolishness,” but there was little he could do to keep his heart from jumping whenever he heard the sound of an engine overhead. He would look upward with the anticipation of a child at Christmas in the hope of catching a glimpse of an airplane winging its way across the sky. Now there were more airplanes and frequent news about aviation records being made—planes flying higher, further, and faster. John knew what was driving his restlessness. He just didn’t know what he could do about it.

From what he read in the newspapers, only army-trained, barnstorming air-gypsies from the Great War, a handful of government and business leaders, and wealthy white playboys actually worked or played with aircraft. How could he learn to fly? He had asked around. Word was there were no black men even working on airplanes, much less flying them. There were plenty of people, black as well as white, who would tell you a black man wasn’t capable of adjusting to the unnatural environment of flight or acquiring aviator skills—meaning they weren’t smart enough to learn.

John first took his money out to Detroit City Airport where he was told “not a chance.” The next weekend he drove out to the corner of Oakwood and Village Road where Ford Field was located. He couldn’t get in the big hangar where they were assembling Ford tri-motor planes. He went down the line of private planes and begged to be taken for a ride, said he would pay, wash the plane, anything. He found that his daddy had been right when he said that the South was not the only place where a black man’s money wouldn’t buy the same things as a white man’s money. It looked to John that what his momma had said years ago, what he had refused to believe, was true: Aviation was closed to blacks. All his life, ever since he could remember, Johnny Robinson longed to experience the joy and excitement and freedom he was sure was part of flight. He could not, would not, go all his life without somehow getting up there to find out for himself. Somehow, I’m gonna fly.

Despondent, John was walking past the Ford hangar when a man called to him, “Hey, boy.” The man was wearing a pair of white, grease-stained overalls.

John didn’t much like the term “boy,” but he stopped. “You calling me?”

The man walked up to John. “I overheard you asking for a ride out on the line,” the man said. “You’re not likely to get a ride around here, but you might have a chance at one of the small fields out in the country. That’s where barnstormers operate, away from government rules and regulations. Maybe you’ll catch a fellow short of cash—most of ’em are. A guy like that might look more at a man’s money than the color of his skin.”

“Why you telling me this?”

“Because I used to be one of ’em, and because maybe I can still remember how I used to ache to get up in the sky.”

“Couldn’t you give me a ride?”

“I could, but I’d take a lot of flack around here for doing it. Sorry, but that’s just the way it is.”

“Well I ain’t gonna give up,” John replied.

The man smiled. “I wish you luck.” He turned and walked off toward a Model-T roadster.

John asked around. One of Fitzgerald’s truck drivers mentioned that he had seen a sign about flying on the road out past Willow Run or Ypsilanti, but he couldn’t remember which.

Early on a Sunday morning in April, John dressed in work pants, a sweater, and jacket—spring was laboring to push winter’s chill from northern Michigan. He drove out of Detroit toward Ypsilanti on a claygravel highway. Out past Willow Run, he found what he was looking for: a sign pointing down a farm road that said “Airplane Rides.” He turned off the main road and after traveling a mile or so came to an open field where a faded red, white, and blue banner strung on a drooping, barbed-wire fence invited one to “Take an Airplane Ride with an Ace.” He pulled off the road, parked by the fence, and got out. A motorbike was parked under a tree but he didn’t see anyone around. John followed a well-worn path leading through a gate and around to the front of a large, weathered barn that had been converted into a hangar. The roof sagged a bit. He could see three airplanes inside, or rather two and a half since the one on the right, shoved toward the back, was disassembled. The fuselage was standing alone, missing its engine. Its wings were propped on edge against the back wall. John recognized that one and th

e one nearest him, which had all its parts but didn’t look much better. They were both Curtiss JN-4Ds, better known as Jennies.

It was the third plane, bright red and clean as a whistle, that caught his eye. It was the most beautiful thing John had ever seen. He called out and got no answer. Nobody was around so he walked into the hangar to get a closer look. John moved carefully around the wing tip and stood by the rear cockpit of the red plane to look inside. He surveyed the instruments, the rudder bar, control stick, seat belt, everything so different from an automobile. The name WACO was painted on the vertical part of the tail. He walked back to the front of the plane. From pictures in one of his books, he figured the engine as an OX5 watercooled model, the same engine that powered the Jenny beside it only this one was mostly hidden by a streamlined cowling. Well, at least airplane engines are not so different from automotive engines I’ve worked on. While he was admiring the plane, he heard a car drive up and two car doors open and shut.

“Hey! You, boy! What the hell you doing fooling around that plane?”

Startled, John swung around to face a short, heavily built, redheaded man with grease stains on his face. He was dressed in soiled khaki pants and a leather jacket. Walking up behind him was a younger man, cleanly dressed in polished riding boots, riding britches, and a blue sweater over a white shirt and tie. He was holding a jacket slung over one shoulder. The young man had a smile on his face. The redheaded man did not.

“Well, boy?” The redheaded man spoke with an Irish brogue.

“I came out here to get a ride. I didn’t see anyone around. I was just looking. I didn’t touch anything.”

“A ride, eh? You come all the way out here to get a ride did you, boy? Would that be because they don’t give rides to niggers at big city airports?”

The fact that what the man said was true hurt John as much as the grossly offensive word “nigger.” John, outwardly quiet, had never been one to look for trouble (friends later couldn’t remember a single fight he had been in except when in the boxing ring at school), but he did have a temper once provoked. He struggled to hold it now. “Look here, mister. I just came out here to pay for an airplane ride. I got the money same as anyone else. I want to see what it’s like, that’s all.”

“Aw, come on, Percy. What the hell you being so grumpy for?” the young man asked. Looking at John, he said, “Percy here has had a bad week. His engine is down.” Turning back to the redheaded Irishman, he offered, “Come on, Percy, drop the whole thing. This fellow didn’t mean anything. Follow me back into town for a beer.”

“Why not? I won’t be making a dime standing here.” He turned to follow the younger man, then turned back to Johnny. “The field’s closed. You came for nothing. Don’t you be messing with anything, boy. Time you be going back where you came from.” He once more turned and walked away, following his friend.

“Hey! Wait a minute!” John called after them. “What’s the trouble with the engine? Maybe I can fix it. I’ll do it for a ride.”

The two men turned to face Robinson. The one named Percy asked, “Now what would you be knowing about an airplane, boy, seeing as how you never been around one before?”

“I got a name and it ain’t ‘boy.’ I’m John Robinson, and I don’t know anything about flying, but I know something about engines. I’m a trained mechanic.”

“Sure you be.” Percy started walking again and rounded the corner of the hangar.

“Percy,” the younger man said with a laugh. “My father’s opinion of all Irishmen is that they are butt-headed, rude, and think with their fists instead of their brains. You trying to prove him right?”

“I’ll tell you what, sonny. I’ll be buying me own beer and you can take your new toy and shove it in someone else’s hangar.”

John hadn’t moved. He could hear them talking though they had disappeared around the corner of the barn.

“Come on, Percy. You can’t afford to buy a beer or anything else. You’re down to one worn-out Jenny with an engine problem. You’re too Irish proud to let me help you out. You can’t get a flying job around here because you got drunk and took your boss’s daughter flying . . . under a bridge for Christ’s sake. And now you won’t even find out if maybe this guy is telling the truth and can put you back in business in time to make a few bucks this afternoon.”

Percy stopped, looked at his companion. Without a word, he turned and walked back around in front of the hangar. “All right, Robinson. Tell me what kind of mechanic work you do.”

“Automotive,” John replied.

“And just how did you get to be a mechanic?”

“Three years of college. I been working nearly two years in Detroit. I put together that car parked out there by the fence, rebuilt the engine.”

“Have you done any brazing work and can you get an outfit?”

Johnny nodded ‘yes’ and answered, “I can borrow an outfit from the shop in town.”

Percy picked up a stepladder leaning against the wall, walked over to the engine of his Jenny, and set the ladder up. “Climb up there and look real close at the neck of the radiator under the filler cap.” Johnny climbed up as he was told. “You see that hairline crack right there near the top?” Percy pointed at the spot.

Johnny nodded. “Looks more like a scratch than a crack.”

“That’s why it took me so long to find it. You start it up and everything works fine. You taxi out, take off. About ten or fifteen minutes into the flight, the engine runs rough and then quits. You glide down and land somewhere, get out, and look it over and find nothing. You prop the engine, it starts right up like nothing’s wrong. I found I had to add a little water the next day. That made no sense. Next day it quit in the air. It was a real thrill for the passenger, I tell you. I could start the engine again, takeoff, and ten minutes later it would quit again. I couldn’t get out of gliding distance from this cow pasture. Finally, I tied the tail to the fence, cranked the engine, set the throttle at about eight hundred revolutions per minute, and let her sit there and run. That’s when I saw the trouble. As soon as this thing gets good and hot, that tiny crack opens up and water spews out of it in a fine spray that blows over the engine from the prop wash. It shorts out the spark plugs, and then the engine starts missing and quits. When it did that while I was flying, by the time I got it down the water had evaporated, the engine had cooled, and that hairline crack was closed up. That’s why I couldn’t find the trouble. Anyway, boy, you get that brazing outfit out here and fix this thing and I’ll give you the ride you want. But you mess up, burn a hole in the radiator, I’ll put more than a hairline crack in your water jacket. You understand me? You better know what you’re doing or don’t fool with it.”

John didn’t care much for the ill-tempered Percy, but he figured he had a chance to do two things. One was to fly for the first time. The other was to show the redheaded bastard that a black mechanic could put him back in business. He looked at Percy.

“It’s a deal. It will take me a while to get to town and back, but I’ll fix it for a chance to fly.”

It was three-thirty in the afternoon when they rolled the faded yellow Jenny out of the hangar.

“Well Robinson, your work is pretty enough. Now we’ll see if it holds. You stand there while Robert gives the prop a twist. You’ll do that for me, will you, Robert?”

While working on the radiator, John had learned that Percy’s friend, Robert Williamson, was fresh out of Harvard and had returned to Detroit to work for his father. Percy had taught him how to fly, a fact Robert’s father still did not know. Robert had paid for his flying lessons and bought the red WACO-9 with money his grandfather had left him, also without his father’s knowledge.

Robert walked up to the prop. “This is your first lesson, John. This is the end that will bite you if you’re not careful. Watch and learn.”

He called out, “Switch off! Throttle closed!”

Percy called back, “Off and closed.”

Although the Jenny’

s tail skid would generally hold the plane in place while the engine idled, the plane had no brakes. Should the throttle be inadvertently left open while cranking, the plane, even with a wheel chocked, could easily run down anyone standing in front of it. The results would not be pleasant.

Robert pulled the propeller through several times. “Switch on! Contact!”

Percy cracked the throttle open a little and repeated, “Contact!”

Robert put both hands on the big wooden propeller, swung his right leg up toward the plane, and, in one fluid motion, swung the leg back as he sharply pulled the prop blade down. The momentum of his right leg swinging out behind him twisted him around and carried him away from the propeller. From there, a couple of steps and he was safely to the side. After three attempts, the engine coughed, burped, and roared alive with a belch of blue smoke, then settled down to a more or less smooth rumble, idling at around 450 revolutions a minute.

Robert pulled the chock from in front of the left wheel and grabbed hold of the outer wing strut. He motioned for John to do the same on the right wing. Percy, after checking to see that his “anchor” men were all set, advanced the throttle. The engine roared, the grass behind flattened in the prop wash, dust and loose leaves swirled behind while the plane shook from wing tip to tail. Robert and John had to dig their heels in to keep the plane from dragging them forward. After what seemed to the two “anchor” men a lot longer than ten minutes, Percy closed the throttle, pulled the fuel mixture control to the Off position, and switched off the magneto. The field was suddenly quiet. Percy jumped down, grabbed the ladder, and ran around front to check the radiator.

“Dry as a bone. ’Tis a good job, Robinson.”

John hardly had a chance to break into a grin before two carloads of chattering young people drove up.

“Hey, Percy! Quit fooling around over there. I’ve brought my Sunday School class out to take a ride with you.”

The voice belonged to a young lady waving from the running board of a shiny touring car that had parked by the fence.

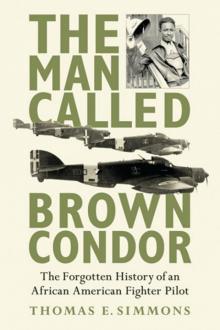

The Man Called Brown Condor

The Man Called Brown Condor